Our second workshop: thoughts from the archives

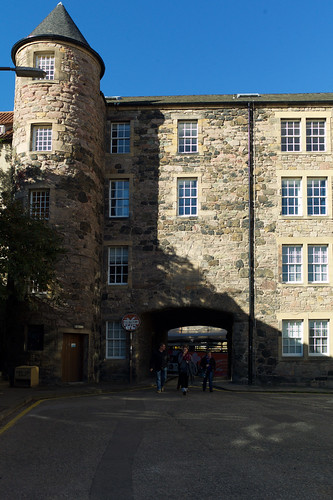

St John’s Land

We had our second project meeting on 15 February at St John’s Land, a part of the University of Edinburgh campus close to the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood. The main topic of discussion was the archives and what our postdocs have been finding there.

It has been approximately one month since our three postdocs began the archival phase of the research. Mike has been at the National Archives at Kew in London; Sara has been at the Archives Nationales at Pierrefitte in Paris; and Elisabeth has been at the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz. Already, they are overwhelmed by the scope, variety and complexity of the data they have been unearthing.

As ever in a project like this, the initial conceptual plan has taken on a different shape depending on the material available. The specificity of administrative archives makes this even more of a problem. The kind of documents that our three postdocs have been seeing are often hard to decipher and even harder to compare.

Still, some patterns are emerging.

Mike has focused much of his attention on the formulation of immigration policy in Britain in the 1960s. He has found extremely rich correspondence between Home Office civil servants and politicians who were still uncertain of exactly how to define the immigration “problem” in the 1960s. In particular, there were sustained discussions over the extent to which Commonwealth preference might help or hinder in the elaboration of effective immigration policy and there was a growing awareness of public dissatisfaction with supposedly “unsustainable” levels of labour immigration.

Yet the exchanges between civil servants and politicians also make clear just how difficult it was to come up with effective strategies to tackle “excessive” immigration. There was a relative absence of punitive measures that could be imposed on immigrants who overstayed or violated the terms of their work “voucher” and there was broad cross-party consensus that the question of immigration should not be overly politicised. Already Mike’s research has shed light on the uncertainty that surrounded the issue at a crucial time in the history of British immigration policy.

A document from the French administrative archives

Sara has also been looking at administrative archives but her focus has been on the period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. Many of her archives come from the French planning department (Commissariat général du Plan) and other government agencies in charge of population, immigration and labour.

From what Sara has read, it is clear that the French government did not problematise the notion of “illegality” in relation to migration until very late in the 1970s, despite the “closing” of the border in the early 1970s. Crucially for our purposes, the reports and correspondence from the archives indicate that there was a lack of statistical data to help analyse migration in France in the 1970s. It was not until the 1980s that the French government began to focus on the phenomenon of illegal immigration specifically. Sara’s research so far suggests fascinating insights into the history of French state rationality, the “turning-point” of the 1970s, and the relative importance of “illegality” as a theme in the history of state monitoring.

Finally, Elisabeth has been wading through hundreds of documents from myriad German government departments charged with monitoring foreigners and migrants in West Germany from the 1950s to the 1970s. Many of these documents have been extremely formal and administrative in tone – German bureaucrats did not correspond in the same jovial way as British civil servants! – but they nevertheless offer invaluable information about how the monitoring of migrants actually took place.

We were all especially interested in the work Elisabeth has been doing on the Ausländerzentralregister (Foreign Central Register), which has its roots in the late nineteenth century but has existed in its present form since 1953. This centralised database collected – and still collects – information about every single foreigner resident on German soil, even though it was not widely known about until it was formalised by constitutional legislation in the 1990s. It therefore gives us an unusual angle from which to analyse how the (West) German bureaucracy approached the question of migration and what sorts of rationalities were at play in the construction and maintenance of such an impressive database in the 1950s and 60s.

As well as telling us more about their research to date, our three postdocs prepared preliminary article proposals based on their archival work, all of which were excellent. There is little doubt that this (at times rather painstaking and tedious) archival phase will lay the foundations for all sorts of innovative and comparative publications.

Watch this space!

Emile